A Silent Health Warning Hiding in Plain Sight: Your Posture

Most adults track their blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood sugar like clockwork. But there’s another health signal that quietly predicts pain, falls, disability, and even lifespan — and almost no one is paying attention to it.

Your posture:

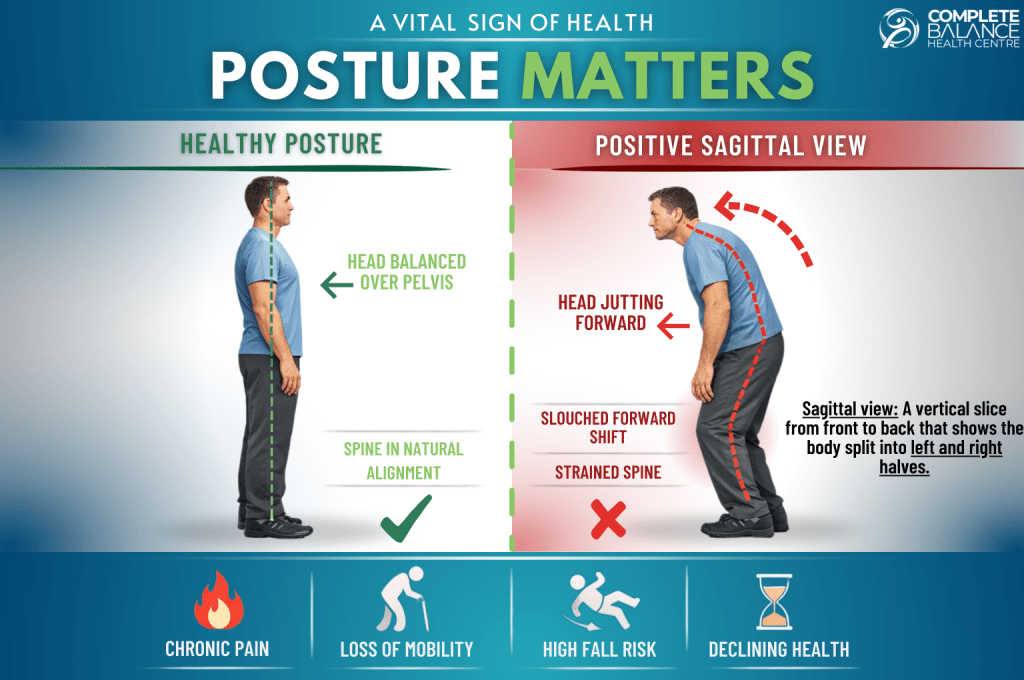

Posture isn’t just about “standing up straight.” It’s a real-time reflection of how well your spine, muscles, and nervous system are working together. When posture begins to change, the effects often develop quietly — long before major symptoms appear.

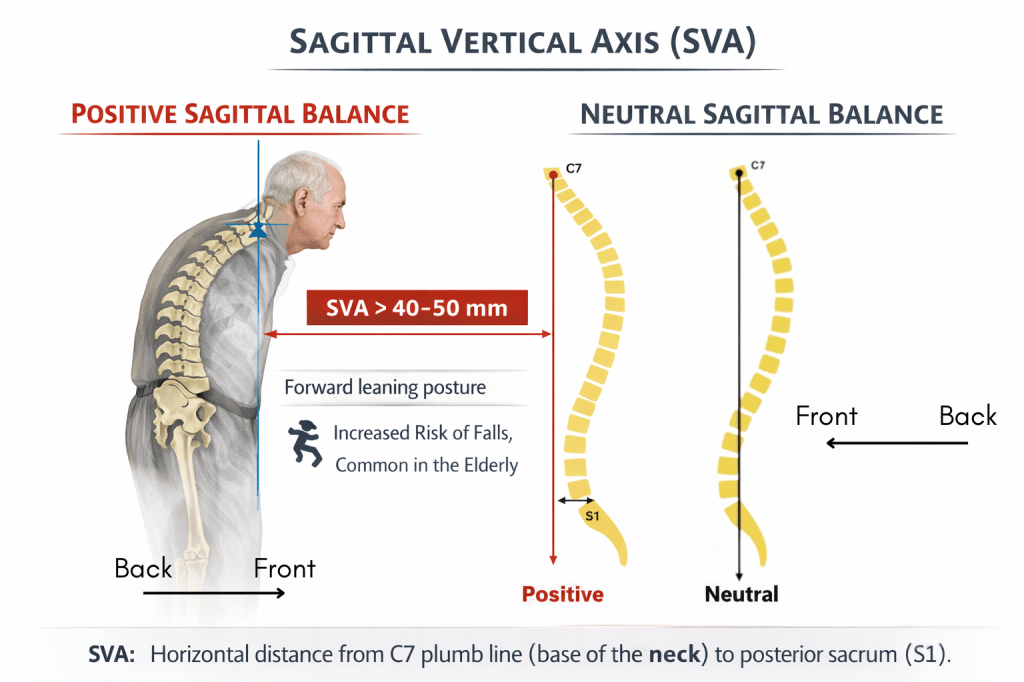

One of the most important posture-related changes clinicians watch for is positive sagittal balance: a forward shift of the upper body away from the spine’s natural alignment. Research shows this forward drift is strongly linked to pain, reduced mobility, falls, and loss of independence.¹

Posture reveals how well the body is coping with daily stress.

What Is Positive Sagittal Balance?

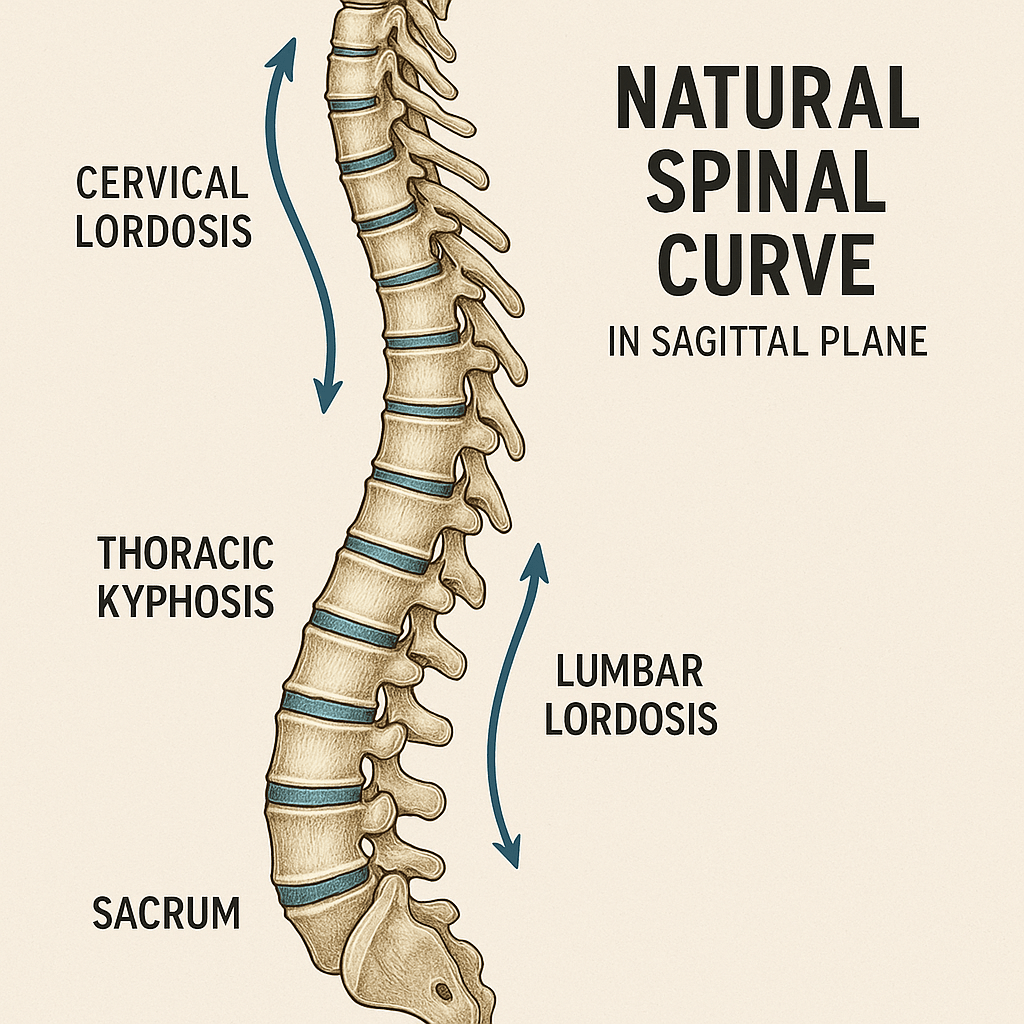

When viewed from the side, healthy posture keeps the head and upper body stacked directly over the pelvis. This balanced alignment allows muscles and joints to work efficiently, conserving energy with every step.

Positive sagittal balance occurs when the upper body drifts forward and can no longer stay centred over the pelvis. This isn’t simple slouching. It reflects deeper spinal and postural changes that make upright posture harder to maintain.

Studies show that adults with significant forward sagittal imbalance report 40–50% worse physical function than those with neutral alignment.² In fact, front-to-back balance predicts pain and disability more strongly than the size of a sideways spinal curve (such as scoliosis) alone.¹

Why This Quiet Change Has Big Consequences

When posture shifts forward, the body’s centre of gravity moves with it. Muscles must stay constantly active just to keep you upright. Over time, this leads to fatigue, reduced endurance, and declining mobility.

Research shows that people with a forward-leaning posture use significantly more energy when walking.³ Everyday activities become more tiring. People often walk shorter distances, move less, and lose confidence in their balance.

This can create a downward cycle: less movement leads to weakness, which worsens posture and further increases fall risk.

Nearly 1 in 3 adults over age 65 falls each year, and falls are the leading cause of injury-related hospitalization in older adults.⁵ When posture contributes to imbalance, falls are more likely to result in fractures, head injuries, and long-term disability.

Forward posture leads to increase fall risk.

Who Is Most at Risk?

Positive sagittal balance becomes more common when the body’s ability to support upright posture is reduced. This can happen when daily physical demands exceed the body’s support capacity over time.

Factors such as prolonged sitting, reduced activity levels, loss of muscle strength, and decreased postural endurance all place greater strain on the spine. When this strain isn’t adequately supported, posture can gradually drift forward.

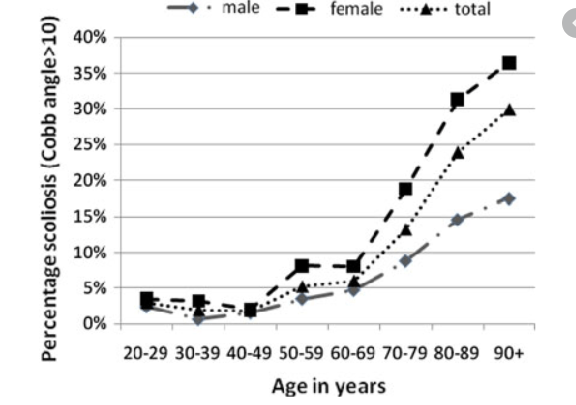

Adults with degenerative spinal conditions, including adult-onset (de novo) scoliosis, are more likely to experience these changes. However, posture decline is not limited to people with a spinal diagnosis.

Research shows that structural and postural changes can begin as early as the 30s, particularly when physical demands, lifestyle habits, and reduced strength combine over time.⁶ This gradual process often goes unnoticed until fatigue, balance changes, or discomfort begin to interfere with daily activities.

Posture changes often develop long before pain appears.

It’s Time to Treat Your Posture Like a Vital Sign

Posture reflects how well the body is adapting to daily demands, physical stress, and aging — much like blood pressure reflects cardiovascular health.

Clinicians increasingly recognize front-to-back spinal alignment as a global marker of function, not just a musculoskeletal concern. When postural changes are identified early, health professionals can:

- Address pain before it becomes chronic

- Improve walking efficiency and endurance

- Reduce fall risk and help preserve independence

Posture tells a story about how the body is aging.

What Can I Do Now?

Postural changes develop gradually — which means they can often be addressed gradually as well, with the right support and long-term approach.

Posture care isn’t about standing straighter for a moment. It’s about building the strength, endurance, and control needed to stay upright during real-life activities.

Working with a local chiropractor or physiotherapist who focuses on postural programs can help ensure care is specific, progressive, and appropriate for your individual needs. Targeted posture and scoliosis programs focus on improving alignment, strengthening the muscles that support upright posture, and building endurance so posture can be maintained throughout the day.

In addition, movement-based practices such as Pilates and yoga can play a valuable supportive role. When practiced appropriately, they help improve body awareness, core strength, flexibility, and postural control. These approaches tend to be most effective when movements are adapted to your posture, emphasize control rather than extreme positions, and complement — rather than replace — a structured posture program.

Paying Attention Early Makes a Difference

Postural changes rarely happen all at once. Fatigue, reduced walking tolerance, or subtle balance changes often appear before significant pain. These early signals are easy to dismiss, but they’re often the body’s way of indicating that support and endurance are starting to decline.

The reassuring part is this: posture is not all-or-nothing. The goal isn’t perfect posture or rigid alignment. It’s a body that can support itself efficiently, move with confidence, and adapt to daily demands over time.

Positive sagittal balance isn’t just “bad posture.” It’s a measurable predictor of pain, mobility loss, falls, and reduced independence. The good news is that posture is observable, measurable, and modifiable — especially when changes are addressed early.

Small, consistent steps, supported by appropriate guidance and movement, can make a meaningful difference.

The earlier posture is addressed, the more options you have.

Your spine doesn’t just support your body —

It supports how long, and how well, you stay independent.

References:

¹ Glassman SD et al.

The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity.

Spine, 2005.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15767888/

² Lafage V et al.

Sagittal alignment parameters influence patient-reported outcomes in adult spinal deformity.

Spine, 2009.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19444063/

³ Le Huec JC et al.

Energy expenditure and sagittal balance.

European Spine Journal, 2011.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21190057/

⁵ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Falls in Older Adults: Important Facts.

https://www.cdc.gov/falls/facts.html

⁶ Adams MA, Roughley PJ.

What is intervertebral disc degeneration, and what causes it?

Spine, 2006.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16508510/